Linearizability, serializability, transaction isolation and consistency models

2016-03-17Linearizability versus Serializability:

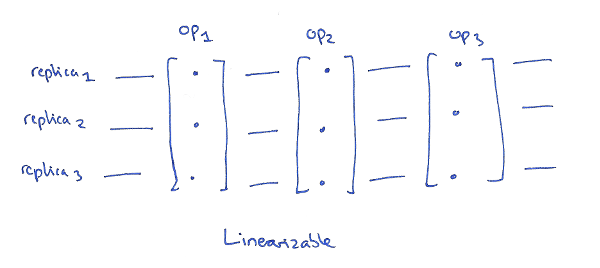

Linearizability is a guarantee about single operations on single objects. It provides a real-time (i.e., wall-clock) guarantee on the behavior of a set of single operations (often reads and writes) on a single object (e.g., distributed register or data item).

Linearizability for read and write operations is synonymous with the term “atomic consistency” and is the “C,” or “consistency,” in Gilbert and Lynch’s proof of the CAP Theorem. We say linearizability is composable (or “local”) because, if operations on each object in a system are linearizable, then all operations in the system are linearizable.

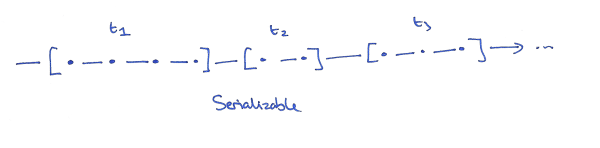

Serializability is a guarantee about transactions, or groups of one or more operations over one or more objects. It guarantees that the execution of a set of transactions (usually containing read and write operations) over multiple items is equivalent to some serial execution (total ordering) of the transactions.

Serializability is the traditional “I,” or isolation, in ACID. If users’ transactions each preserve application correctness (“C,” or consistency, in ACID), a serializable execution also preserves correctness. Therefore, serializability is a mechanism for guaranteeing database correctness.

Distributed Consistency and Session Anomalies:

In the database systems community, the gold standard is serializability. We’ve spent plenty of time looking at this in the last couple of days. Serializability concerns transactions that group multiple operations across potentially multiple objects. A serializable schedule is one that corresponds to some ordering of the transactions such that they happen one after the other in time (no concurrent / overlapping transactions). It’s the highest form of isolation between transactions.

In the distributed systems community, the gold standard is linearizability. Linearizability concerns single operations on single objects. A linearizable schedule is one where each operation appears to happen atomically at a single point in time. Once a write completes, all later reads (wall-clock time) should see the value of that write or the value of a later write. In a distributed context, we may have multiple replicas of an object’s state, and in a linearizable schedule it is as if they were all updated at once at a single point in time.

Also, small correction: the “C” in ACID is the assumption that the application program is correct (each transaction in isolation brings the database from a correct state to another correct state), whereas the AID properties are guarantees provided by the database. Together they imply serializability.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Consistency_model:

Strict consistency is the strongest consistency model. It requires that if a process reads any memory location, the value returned by the read operation is the value written by the most recent write operation to that location.

The sequential consistency model as defined by Lamport(1979) is a weaker memory model than strict consistency.

Linearizability (also known as atomic consistency) can be defined as sequential consistency with the real-time constraint.

Causal consistency can be considered a weakening model of sequential consistency by categorizing events into those causally related and those that are not. It defines that only write operations that are causally related must be seen in the same order by all processes.

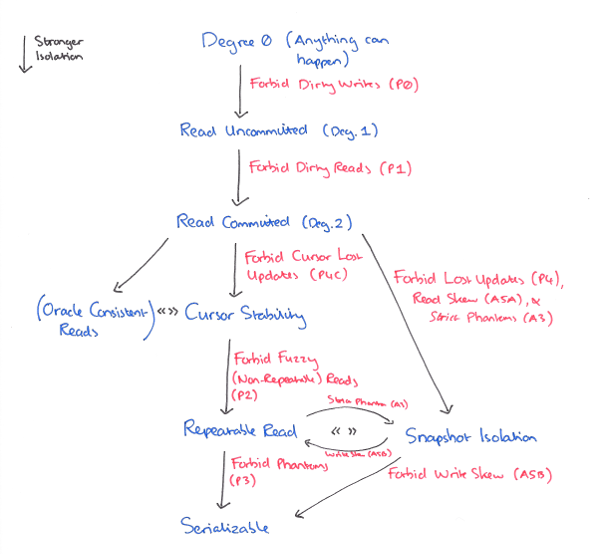

A Critique of ANSI SQL Isolation Levels:

Other articles: